On February 26, 1966, at St. Joseph’s Hospital in Burbank

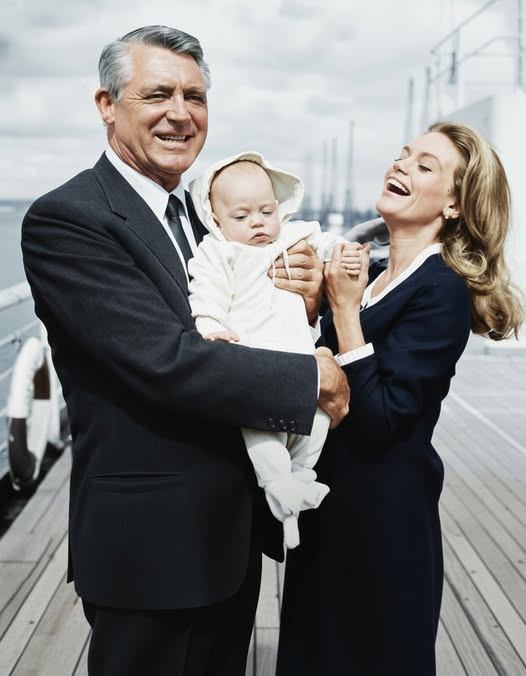

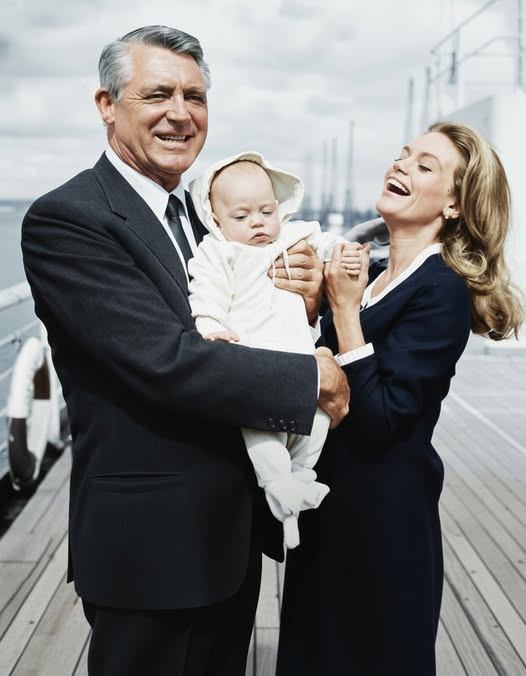

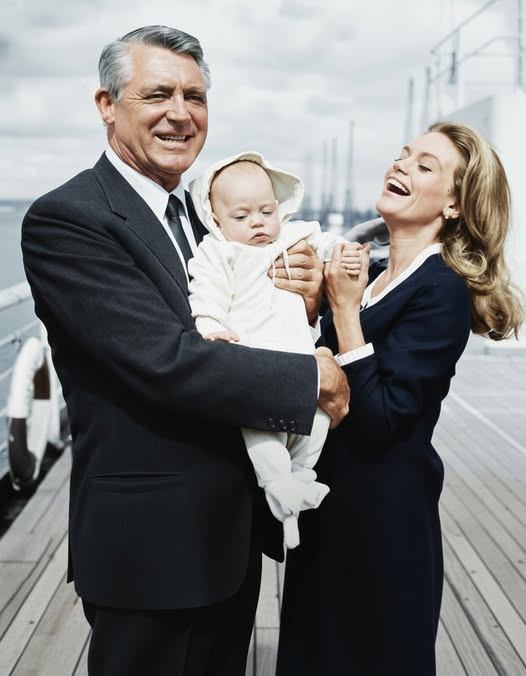

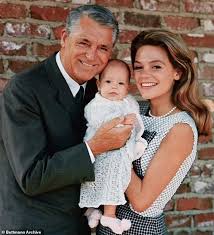

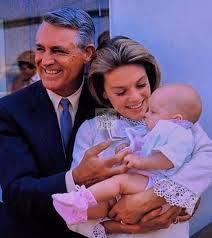

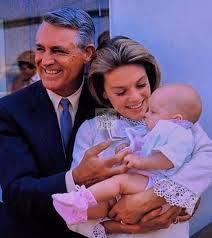

On February 26, 1966, at St. Joseph’s Hospital in Burbank, California, sixty-two-year-old Cary Grant became a father for the first time. His wife, twenty-eight-year-old actress Dyan Cannon, had just delivered a daughter they named Jennifer. Grant stood in the hospital room, holding this tiny, fragile life, and something inside him shifted in a way he had never expected.

Within months, he walked away from acting altogether. His final film, Walk, Don’t Run, was already complete. At the height of global fame—when he could have spent another decade on-screen—one of Hollywood’s most iconic leading men simply stopped. “I could have gone on acting and playing a grandfather or a bum,” he later said, “but I discovered more important things in life.”

It sounds like the perfect Hollywood ending: the legend who chose fatherhood over fame, who traded premieres for bedtime stories, who finally found meaning in raisi ng his daughter. And in certain ways, that version is true. But it is not the whole truth.

ng his daughter. And in certain ways, that version is true. But it is not the whole truth.

ng his daughter. And in certain ways, that version is true. But it is not the whole truth.

ng his daughter. And in certain ways, that version is true. But it is not the whole truth.The real story is harder, darker, and far more human. It is about a man who could be tender and terrible, who adored his daughter but failed at marriage, who tried desperately to outrun the wounds of his childhood and often pulled others into the turbulence. It is about how someone can be a loving parent while still being a deeply flawed partner, and how children can be cherished even when born into chaos.

Grant—born Archibald Leach in the slums of Bristol in 1904—spent his life constructing an illusion. As a boy, he lost his mother without explanation; his father secretly placed her in an asylum and told him she had died. He rebuilt himself from that grief and poverty into the polished ideal of charm and masculine sophistication. He mastered the appearance of effortless ease while burying scars that never fully closed.

By the time he met Dyan Cannon, he had already been married four times. His first marriage ended when Virginia Cherrill accused him of striking her. Now, at sixty-one, he fell for Cannon after seeing her on television, and pursued her with an intensity that overwhelmed her. He flew to every city where she performed in How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying. They married in Las Vegas on July 22, 1965. She was pregnant almost immediately.

Yet even as he prepared to become a father, the marriage was coming apart. Cannon later wrote, in Dear Cary, that Grant was controlling in ways that felt both subtle and suffocating. He wanted to reshape her—her hair, her clothes, her walk, even the way she wrote. He asked her to quit acting. She did, hoping to please him. “He didn’t know how to be happy,” she would later say.

Grant had been experimenting with LSD since the late 1950s in guided sessions with radiologist Mortimer Hartman. He believed the drug helped him peel back layers of old trauma. By the time he married Cannon, he was convinced LSD could fix anything. He pushed her to take it with him, arguing that it would “enlighten” her and save their marriage. She later testified that he was an “apostle of LSD,” still using it in 1967 as a cure-all for their troubles.

In August 1967, with Jennifer just seventeen months old, Cannon separated from him. She filed for divorce a month later. The proceedings were bitter. Cannon asked the court to limit Grant’s access to Jennifer. Accounts from the divorce—memoirs, transcripts, later interviews—described verbal and physical abuse, painting a picture of a man whose impeccable charm could turn into explosive anger behind closed doors.

The divorce was finalized on March 21, 1968. Jennifer was only two.

And yet, from this wreckage emerged something unexpectedly profound. Grant became a devoted, attentive father. The same man who had been controlling and harmful as a husband poured his energy and tenderness into becoming the parent he wished he’d had.

The custody arrangement, initially tense, slowly evolved. Jennifer lived primarily with Grant but spent regular time with both parents—weekends, summers, unstructured days. Over time, Grant and Cannon found a fragile peace, a functional form of co-parenting. “The first and most important thing is that I instilled in Jennifer that the divorce was not her fault,” Cannon said. “We both loved her dearly. It was OK for her to love us both.”

Grant embraced fatherhood with near-obsessive devotion. Having lost all his childhood keepsakes when his family home in Bristol was destroyed during World War II, he became determined to preserve every piece of Jennifer’s life. He saved her notes, drawings, report cards. He filmed home movies, took countless photos, recorded hours of conversations. He built a fireproof vault into the house to store it all.

He picked her up from school. He read to her. He taught her how to tie a tie. One Halloween, he rented a house in her favorite trick-or-treat neighborhood just to see her in costume. He took her to Dodgers games and the racetrack. He turned his old cufflinks into earrings for her. He called her his “best production.”

“My life changed the day Jennifer was born,” he told biographer Graham McCann. “I’ve come to think the reason we’re put on this earth is to procreate. To leave something behind. Not films—they won’t last. But another human being. That’s what matters.”

Jennifer remembered a father who was playful and gentle, curious about the world, fiercely attentive. In her memoir Good Stuff—named after his favorite expression for happiness—she writes about listening to Stravinsky on the front lawn, laughing through board games, traveling to Monaco to visit Grace Kelly. She remembers notes hidden in her lunchbox, wise jokes, and quiet moments of unexpected honesty. “Given the pain of his upbringing,” she told The Guardian in 2023, “he could have self-destructed. But he wanted to make sure he didn’t repeat the pattern.”

The house at 9966 Beverly Grove Drive, a farmhouse tucked into Beverly Hills, became the center of her childhood. When Grant married Barbara Harris in 1981—forty-seven years younger than he—Jennifer gained a stepmother she grew close to. Grant remained active in business, serving on boards for Fabergé, MGM, and others. He frequently chartered the company plane to visit Cannon’s film sets just to spend a day with Jennifer.