The pink layette sat folded in the dresser drawer, carefully prepared like all the others before it

The pink layette sat folded in the dresser drawer, carefully prepared like all the others before it. Therees Brooks was thirty-nine years old and about to give birth to her fourteenth child in their remodeled schoolhouse in Pittsfield, Maine. She knew what to expect. After thirteen daughters, the pattern seemed unbreakable. The oldest girls had already picked out names—probably another girl’s name, something that would fit with Eunice, Alma, Elaine, Ervena, Rosalie, the twins Janet and Janice, Donna, Hazel, Rae Jean, Eleanor, Koyce, and little Lorraine who was barely eighteen months old herself.

October 24, 1954 started like any other morning in the Brooks household. Sixteen-year-old Eunice helped with the younger ones. The ten-year-old twins corralled their middle sisters. The three-year-old clung to whoever would hold her. And Lloyd Brooks, a truck driver earning fifty dollars a week, prepared for another daughter to join their already spectacular collection. Before Leslie’s arrival, the Brooks family held a peculiar distinction: they were known as the largest all-girl family in America. Thirteen daughters, all healthy, all living under one roof in a building that used to educate other people’s children. Now it served as a testament to biological probability—or improbability, depending on how you counted.

Then Therees went into labor, and everything changed.

The baby arrived at home, as all the others had. But this time, when the midwife made the announcement, the room fell silent for a moment before erupting in astonished laughter. A boy. After thirteen girls spanning sixteen years, the Brooks family finally had a son. They named him Leslie Benjamin, and suddenly all those pink clothes, all those girl’s toys, all that accumulated feminine wisdom became a curiosity rather than preparation. Nobody quite knew what to do with a boy.

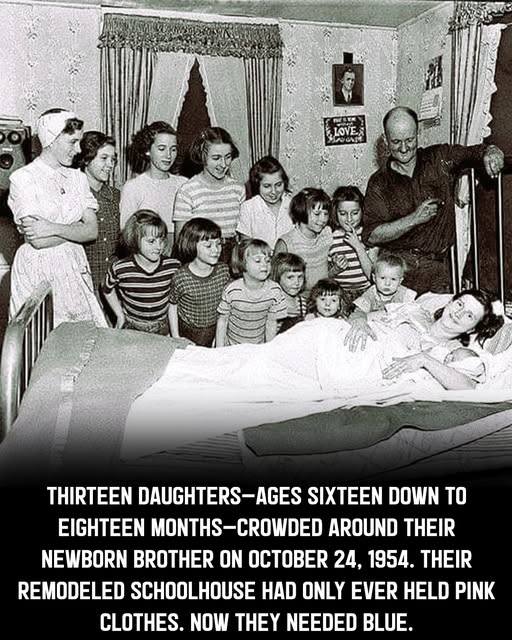

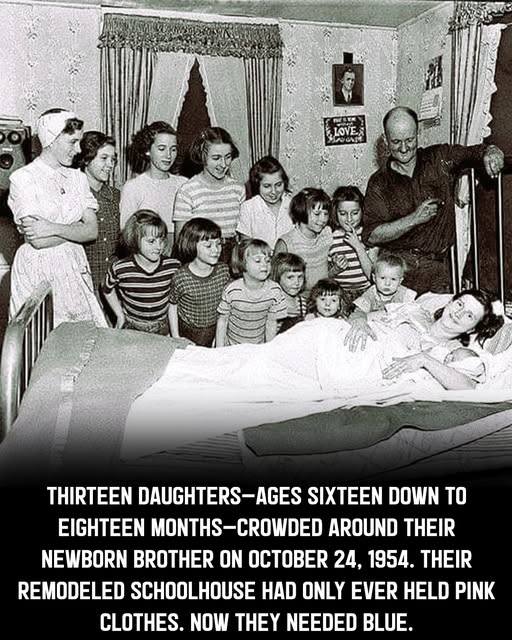

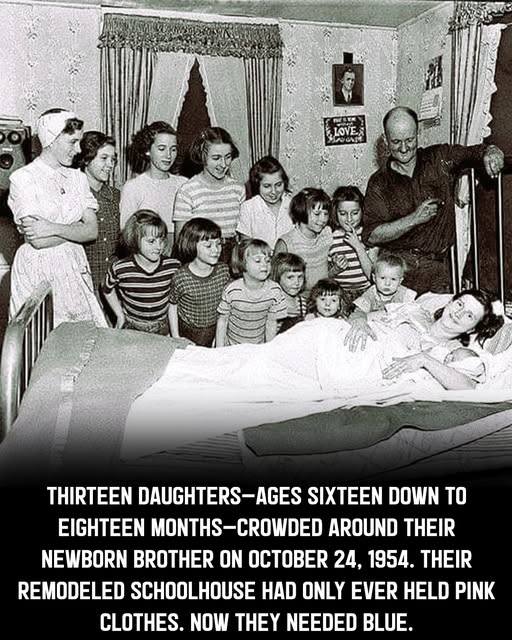

The Associated Press photographer J. Walter Green heard about the story—of course he did. A family with thirteen daughters and finally a son? In 1954, this was headline material. He arrived at the remodeled schoolhouse to capture what would become one of the most iconic family photographs of the decade. The image is almost overwhelming in its composition: thirteen girls, ranging from a teenager to a toddler, all crowded around their exhausted mother who holds a tiny bundle. And standing behind them all, Lloyd Brooks, looking simultaneously proud, bewildered, and perhaps a little terrified at what the universe had just handed him.

“Now that I have a boy, I hope it will be the end,” Lloyd told reporters. He said it with the weary humor of a man who understood that fourteen children on fifty dollars a week was already stretching the definition of possible. Therees, holding Leslie in the photograph, wore the expression of a woman who had just accomplished something statistically remarkable—though whether she was pleased about it remained diplomatically unspoken.

The photograph went national immediately. Newspapers across America published the image with variations of the same headline: “Maine Family’s All-Girl Record Broken.” It captured something essential about 1950s America—large families were common but not this large, and certainly not this lopsided. The Brooks children became minor celebrities. The story appeared in papers from coast to coast, each reporter marveling at the improbability: thirteen daughters followed by one son.

But behind the charming photograph and the newspaper headlines lay a more complex reality. The Brooks family lived in genuinely difficult circumstances. Lloyd’s truck driving job barely supported his massive family. The remodeled schoolhouse, while spacious enough for their needs, was a converted building rather than a proper home. The older girls almost certainly helped raise the younger ones—Eunice at sixteen was practically a third parent. The clothing was passed down from oldest to youngest until it disintegrated. The hand-me-downs that had flowed so efficiently through thirteen daughters would stop completely with Leslie. He would need new clothes, boy’s clothes, items the family had never purchased before.

The twins, Janet and Janice, were ten years old when Leslie arrived. Imagine their perspective: they’d spent their entire lives in a household of girls, where everything from chores to secrets was divided along familiar lines. Now suddenly there was a boy, a curiosity, someone fundamentally different in a family where sameness had been the defining characteristic. Eight-year-old Donna, seven-year-old Hazel, five-year-old Rae Jean—all these middle daughters who had always had older sisters to emulate and younger sisters to guide—now had a brother, a concept that existed only in other families, never in their own.

And what about little Lorraine, just eighteen months old when Leslie was born? She would grow up with a brother, never fully remembering the time when the Brooks family was exclusively female. For her, Leslie wouldn’t be the miraculous boy after thirteen girls; he would simply be her younger brother, unremarkable in his maleness because she’d never known anything else.

The photograph that appeared in newspapers showed thirteen pairs of eyes fixed on the baby with expressions ranging from wonder to wariness. Some of the older girls smiled with genuine delight. Some of the younger ones looked confused, unsure what all the fuss was about. Little Koyce, three years old, reached out toward the bundle as if trying to understand what had changed. And Lloyd stood in the back, his face betraying the mix of emotions that come with being the father of fourteen children: love, exhaustion, pride, and an unmistakable hint of “what have we gotten ourselves into?”