August 14, 1958, started like any other night at Methodist Hospital in Memphis

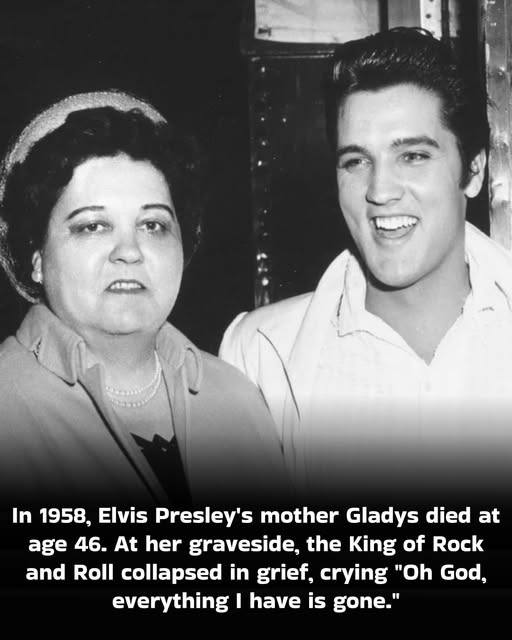

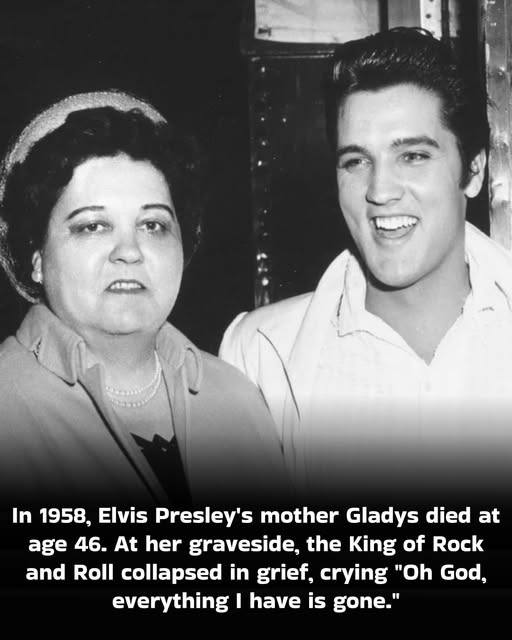

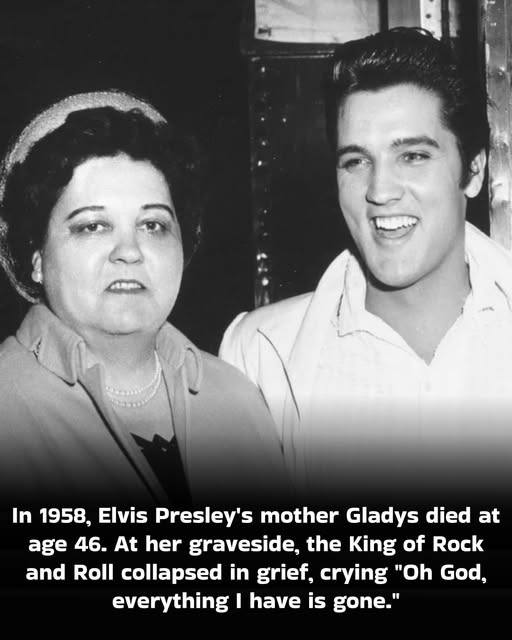

August 14, 1958, started like any other night at Methodist Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee. But at 3:15 in the morning, a heart gave out. Gladys Love Presley, mother of the world’s most famous entertainer, died at age 46 from a heart attack brought on by acute hepatitis. Her husband Vernon was at her side. Her son Elvis, the man who’d bought her a mansion and given her everything money could buy, had just left the hospital hours earlier.

When Elvis arrived at the hospital that morning and learned his mother was gone, witnesses said he sank to his knees beside her bed and wept. “She was all we lived for,” he sobbed. “She was always my best girl.”

The bond between Elvis and Gladys wasn’t just close—it was the foundation of everything he was. Born on January 8, 1935, in a tiny two-room house in Tupelo, Mississippi, Elvis came into the world as a twin. His brother, Jesse Garon, was stillborn. From that moment, Gladys believed Elvis had absorbed the strength of both boys. She poured into him twice the love, twice the protection, twice the devotion. She would give him pet names. They spoke in baby talk well into his teenage years. Due to poverty, they even shared a bed throughout his adolescence.

When Vernon was briefly imprisoned for forging a check in 1938, mother and son grew even closer. Gladys would drag baby Elvis in a sack beside her as she worked the cotton fields. When she walked two miles to work each day, Elvis was never far from her thoughts. They were everything to each other—a relationship so intense it would shape the rest of Elvis’s life.

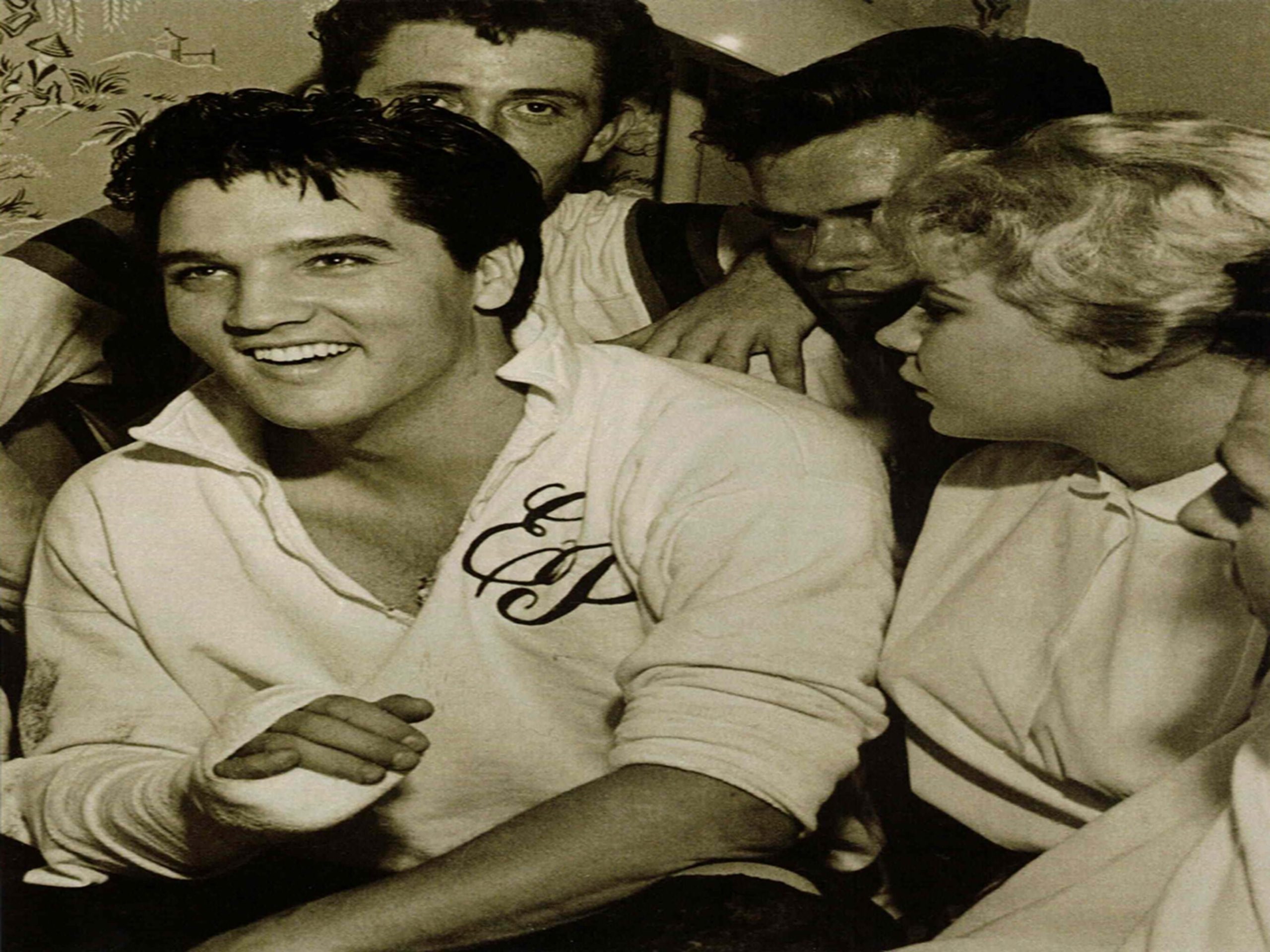

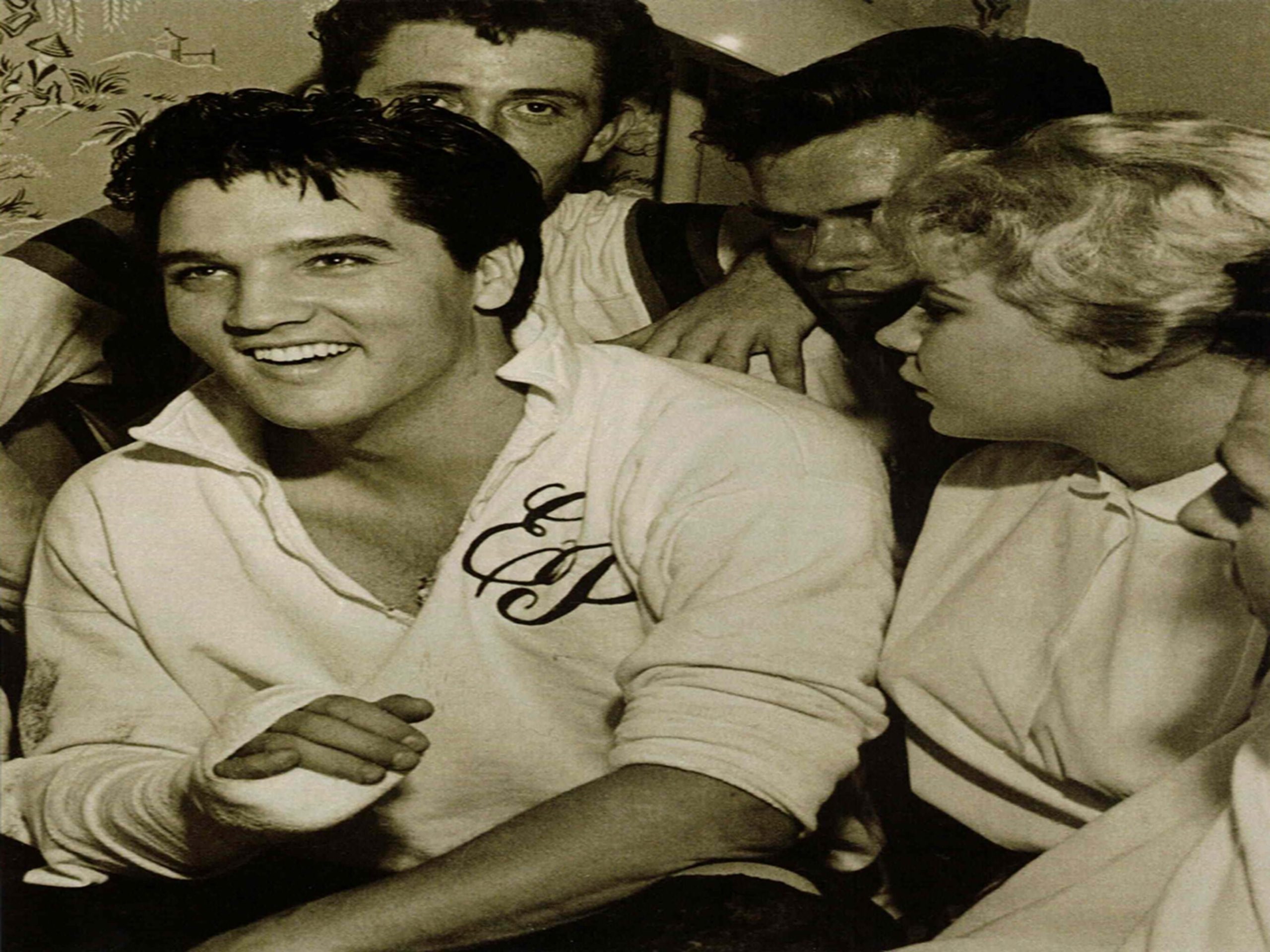

As Elvis rose to stardom in the 1950s, he never forgot where he came from. His first priority was always his mother. When the money started flowing in, he insisted on buying his parents a home—first a modest house, then eventually the grand estate that would become known as Graceland. “Early in his career, when the golden flood began, he insisted on his parents living in luxury and comfort,” one newspaper reported.

But fame was hard on Gladys. While immensely proud of her son, she found the spotlight unbearable. Neighbors at Graceland reportedly mocked how she did her laundry outdoors. Elvis’s team asked her to stop feeding chickens on the lawn. The woman who’d worked so hard to give her son everything now felt out of place in the mansion he’d bought her. “I wish we was poor again, I really do,” she told a friend.

Depression set in. Gladys began drinking heavily and taking diet pills. By 1958, she had developed hepatitis, her liver slowly failing. In early August, while Elvis was stationed at Fort Hood, Texas, during his Army service, Gladys’s condition deteriorated rapidly. On August 9, an ambulance rushed her from Graceland to Methodist Hospital, where doctors listed her condition as grave.

Elvis frantically tried to get emergency leave. It took more effort than it should have for any ordinary soldier—calls from Gladys’s doctor to military personnel in Washington, and Elvis’s desperate threat to go AWOL if they didn’t let him see his dying mother. Finally, on August 12, he was granted leave. He flew from Fort Worth to Memphis and went straight to the hospital.

When Elvis entered his mother’s hospital room that night, Gladys cried out, “Oh, my son, oh, my son.” He spent all day Wednesday, August 13, at her side. That evening, exhausted, he finally went home to rest. Vernon stayed with her through the night. In the early morning hours of August 14, she struggled for breath. Vernon called the doctor, but Gladys was gone before he arrived.

The funeral was held at Memphis Funeral Home on August 15, at 3:30 PM. Elvis wanted the service at Graceland, but Colonel Parker convinced him that security wouldn’t be able to handle the crowds. Gladys’s favorite gospel group, the Blackwood Brothers, performed. Elvis sobbed hysterically throughout the service. He could barely stand.

At Forest Hill Cemetery, as they prepared to lower his mother into the ground, Elvis completely broke down. He leaned over the grave, crying out words that would echo through the decades: “Goodbye, darling, goodbye. I love you so much. You know how much I lived my whole life just for you.” And then, the cry that summed up everything: “Oh God, everything I have is gone.”

He could barely walk after burying her. Friends and family had to support him. People who knew Elvis well would later say he was never the same. The loss of Gladys created a void that nothing—not fame, not success, not love—would ever fill.

Yet even in his deepest grief, Elvis’s fans showed him extraordinary compassion. In the days following Gladys’s death, he received more than 100,000 cards and letters, around 500 telegrams, and more than 200 floral arrangements expressing sympathy. The outpouring of support briefly softened even some of his harshest critics, who had previously dismissed him as a corrupting influence on American youth.

To understand Elvis Presley’s talent is to understand what made him truly exceptional. He possessed a voice covering approximately two and a half octaves—from a baritone low-G to a tenor high-B, with falsetto extension even higher. Music critics described it as “variable and unpredictable” at the bottom, “often brilliant” at the top, with the capacity for “full-voiced high-Gs and As that an opera baritone might envy.”

But Elvis’s genius went beyond technical range. As one scholar noted, “His voice had an emotional range from tender whispers to sighs down to shouts, grunts, grumbles and sheer gruffness that could move the listener from calmness and surrender to fear.” He could seamlessly shift between tenor and baritone voices, moving effortlessly across genres—rock and roll, country, blues, gospel, and pop—with an authenticity that stunned audiences.

Gospel music was his truest passion. It was the music of his childhood in the Assembly of God church, the music that moved him to tears, the music where his voice found its purest expression. In a career filled with historic achievements, Elvis won only three Grammy Awards in his lifetime—all three for gospel recordings. “How Great Thou Art,” his 1967 gospel album, earned him his first Grammy. It wasn’t the commercial hits that earned him the music industry’s highest honor, but the sacred songs he sang from the depths of his soul.

Elvis’s humility about his gifts was genuine. He never sought to dominate a stage or overshadow other musicians. Instead, he surrounded himself with the finest talent he could find, constantly chasing a sound that felt authentic and alive. His photographic memory allowed him to absorb musical styles instantly, picking up melodies and vocal techniques just by hearing them once.

But perhaps more remarkable than his talent was his character. Elvis Presley was famously, quietly generous. He would visit hospitals without press coverage, send gifts to complete strangers, and help people he’d never met. Stories of his kindness are legendary—buying cars for people who admired them in dealerships, paying off strangers’ mortgages, funding medical treatments for people he’d never see again.