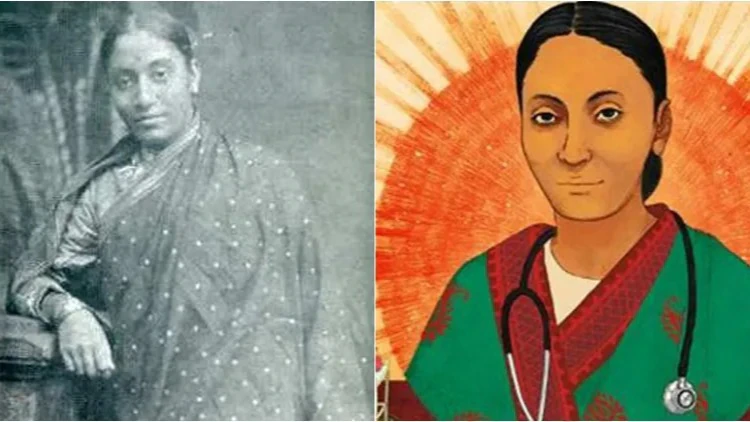

The Woman Who Chose Prison Over Child Marriage — And Transformed a Nation

The Woman Who Chose Prison Over Child Marriage — And Transformed a Nation

Bombay, India — March 1887.

Inside a crowded colonial courtroom, 23-year-old Rukhmabai stood before Judge Robert Hill Farran as he delivered a ruling that would ignite debate across an empire. Her fate, he said, rested on two choices: return to the man she had been married to at the age of eleven, or face six months in prison.

The courtroom fell silent. Her answer did not.

“I would rather go to prison than live with a man I was forced to marry as a child.”

Those words, spoken without hesitation, traveled across continents. They challenged British lawmakers, shook conservative Indian society, and sparked one of the most important debates of the 19th century: whether a girl could be forced into marriage and denied the right to consent.

Rukhmabai’s life had begun in the shadow of the very tradition she would later resist. Born in 1864, she was the daughter of Jayantibai—a widow by the age of seventeen after being married at fourteen and becoming a mother at fifteen. Determined to give her daughter a different life, Jayantibai remarried Dr. Sakharam Arjun, a respected reformer who believed girls deserved education, dignity, and opportunity.

Under his guidance, Rukhmabai was raised to value her intellect. But even progressive households were not entirely immune to the pressures of tradition. At eleven, her maternal grandfather arranged her marriage to Dadaji Bhikaji, an older boy of nineteen. Rukhmabai refused to move into his home and continued living with her mother and stepfather, pursuing her studies quietly and determinedly.

Years later, as Dadaji fell into debt and drifted away from education, he returned with a demand rooted in ancient custom: he sought “restitution of conjugal rights,” insisting the court compel her to live with him.

Rukhmabai refused.

Girls, she argued, cannot consent at eleven.

No woman belongs to a man simply because custom says so.

Judge Joseph Pinhey agreed. In 1885, he ruled that marriage without valid consent could not be enforced. The verdict sent shockwaves through India. Reformists celebrated her courage. Conservative leaders condemned her defiance. Newspapers across the British Empire published heated editorials.

The case was appealed under political pressure, and Judge Farran overturned the ruling in 1887. Yet the young woman who had already endured twelve years of litigation did not falter. When given her ultimatum—marriage or prison—she chose prison.

Her courage reached London, where it came to the attention of Queen Victoria herself. Under her pen name, “A Hindu Lady,” Rukhmabai wrote essays condemning child marriage and urging legal reform. Public pressure mounted until, in 1888, a settlement was reached: Dadaji accepted 2,000 rupees to relinquish all claims to her.

Rukhmabai was finally free.

And freedom, for her, was not the end but the beginning.

She traveled to England to study medicine—an extraordinary step for an Indian woman of the time. In 1894, she returned to India as one of the nation’s first female physicians. For decades, she treated women of every caste, helped train nurses, worked through epidemics, and continued to advocate for the protection of young girls.

Her case played a pivotal role in shaping the Age of Consent Act of 1891, which raised the minimum age of consent and marked the first major legal victory against child marriage in India.

Rukhmabai died on September 25, 1955, at ninety years old. She outlived the man who tried to claim ownership over her life, outlived the empire that governed her youth, and outlived the social order that once demanded her silence.

Her legacy lives on in every girl allowed to remain a child, every woman free to choose her own path, and every voice strong enough to say “no” when the world insists on “yes.”