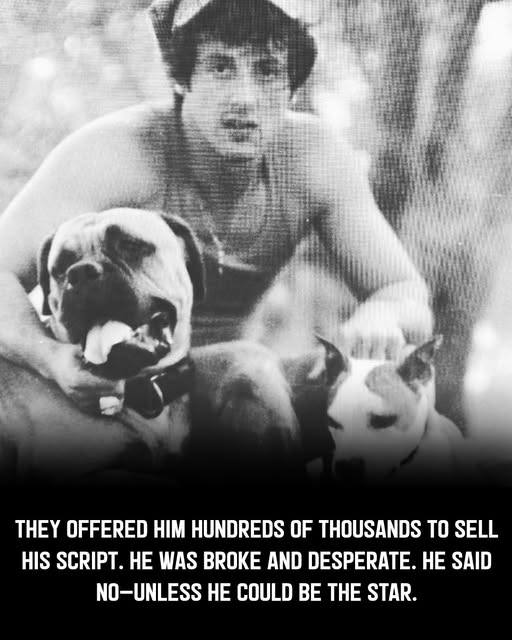

They offered him hundreds of thousands to sell his script.

They offered him hundreds of thousands to sell his script. He was broke and desperate. He said no—unless he could be the star.

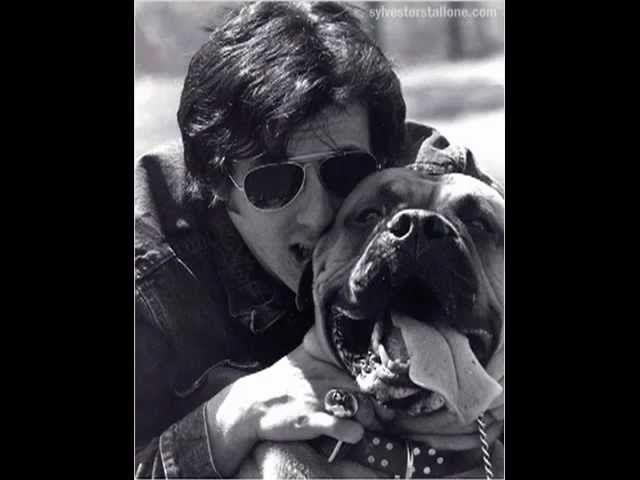

In 1975, Sylvester Stallone was 29 years old and failing.

He had been trying to make it as an actor for nearly a decade. Small roles. Bit parts. Background characters in forgettable films. Audition after audition where casting directors took one look at his face and moved on.

His face was the problem, they said. Or part of it.

When Stallone was born, the doctors used forceps during delivery. They slipped. The forceps severed a facial nerve, leaving the left side of his face partially paralyzed. His mouth drooped. His speech was slurred. His expression was lopsided.

In Hollywood, where faces were currency, Sylvester Stallone’s face was considered worthless.

He kept trying anyway. He took acting classes he couldn’t afford. He went to auditions where people barely looked at him. He worked odd jobs—cleaning lion cages at the zoo, ushering at a movie theater, anything to survive while chasing the dream.

By 1975, he was broke. Actually broke. Not Hollywood “struggling actor” broke—genuinely unable to pay rent broke. His wife Sasha was working multiple jobs to keep them afloat. They fought constantly about money, about his refusal to give up, about whether this dream was ever going to work.

Stallone was running out of time and options.

Then, on March 24, 1975, he watched a boxing match on television.

Muhammad Ali versus Chuck Wepner. The champion against a journeyman fighter no one expected to last more than three rounds. Wepner was a working-class guy, a liquor salesman from New Jersey, not a professional athlete in Ali’s league.

Everyone expected a massacre.

Instead, Wepner lasted fifteen rounds. He even knocked Ali down in the ninth round. He took punch after punch and kept getting up. He lost the fight, but he went the distance with the greatest boxer alive.

Stallone watched this nobody refuse to stay down against impossible odds.

And something clicked.

He went home that night and started writing. Three and a half days later, he had a screenplay. Ninety pages about a nobody boxer from Philadelphia who gets a shot at the heavyweight champion. A guy who knows he can’t win but fights anyway, just to prove he’s not another bum from the neighborhood.

He called it Rocky.

Stallone knew the script was good. He knew it had something special—that underdog energy, that working-class desperation, that refusal to quit even when quitting made sense.

He also knew something else: he had to play Rocky Balboa.

Not because he was a great actor. Not because he had proven himself. But because he was Rocky Balboa. The working-class guy with the messed-up face that Hollywood didn’t want. The fighter who kept showing up even when everyone said he should quit.

If someone else played Rocky, the movie might be good. But it wouldn’t be true.

Stallone’s agents started shopping the script around Hollywood. And Hollywood loved it.

Producers saw the potential immediately. This was a crowd-pleaser. An underdog story. Oscar material. They started making offers.

$75,000 for the script. Then $100,000. Then more.

There was just one condition: Sylvester Stallone couldn’t star in it.

They wanted Ryan O’Neal. Or Burt Reynolds. Or James Caan. Real actors. Bankable stars. Not some unknown with a paralyzed face who had mostly appeared in exploitation films.

The offers kept climbing. $150,000. $200,000. Some reports say they went as high as $360,000.

For a guy who couldn’t pay his rent, who was watching his marriage crumble under financial pressure, who had been scraping by for years—this was life-changing money.

Take the money. Sell the script. Walk away with more cash than you’ve ever seen. Let real actors make your movie.

Stallone said no.